ABY.H | New Horizons and the Voyager Probes

We’ve sent spacecraft to explore as much of the solar system as we can — these are the stories of the ones that have gone the furthest.

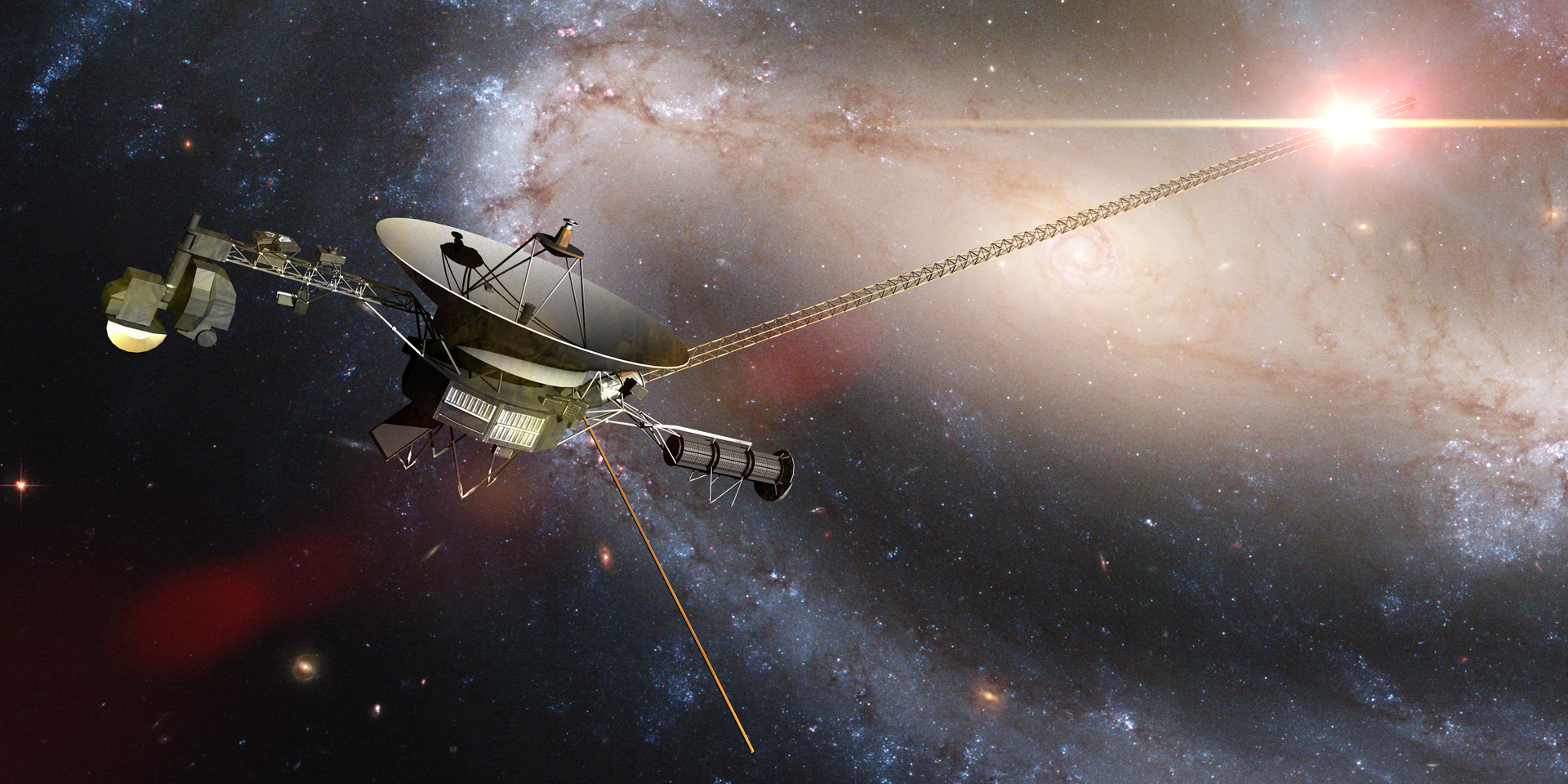

Voyager 1 & 2

The story of the Voyager probes began because the planets were in alignment, literally. It continued through unexpected difficulties. It revealed a wealth of astonishing discoveries. It finished on a note of hope from our entire species.

The Mission

Once every 176 years, the outer planets line up in such a way that the are close enough to each other to be used to slingshot a spacecraft from one to the other. If not for this, the mission could never have worked. Though NASA was only originally given permission to go to Jupiter and Saturn, the scientists hoped that the mission would be successful enough to continue on to the outermost planets as well. In 1972, they began to prepare the mission, building two identical spacecraft to increase the odds of success.

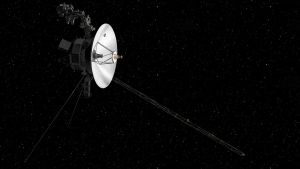

Each of the Voyager spacecraft was about the size of a small school bus, weighing over 1750 pounds, with a main antenna that was about 12 feet in diameter, multiple cameras, and 11 other scientific instruments. All together, each had 65,000 parts.

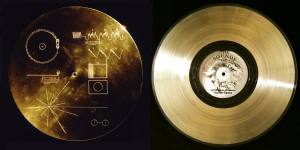

And each had something unique, something that has never been part of a spacecraft before or since: the Golden Record. True, Pioneer 10 and 11, which launched in 1972 and 1973, both had a simple plaque with line drawings of human figures and a basic “map” of how to find Earth. But the Golden Record could hold vastly more information in the same amount of space. With its music, photos, and greetings from around the world, it was a way to tell any other beings in the universe, “hey—this is us.”

The Launches

Wait — Voyager 1 launched after Voyager 2? Yes, but because Voyager 1 was on a faster trajectory, it overtook Voyager 2 within months, and after that, was always ahead.

Jupiter

The first leg of the journey was 400 million miles to Jupiter, and in January of 1979, Voyager 1 made its approach, with Voyager 2 just four months behind. It was there that another last minute improvisation was put to the test. Realizing just two months before launch that radiation from Jupiter’s magnetic field could damage Voyager’s electronics, scientists scrambled to protect all of Voyager’s outside cabling. But there was no way to get materials through regular channels, so they used aluminum foil, the same kind that you can buy in any grocery store today.

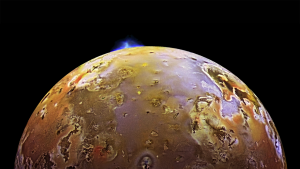

Luckily, Voyager came through unscathed, getting the first sight of Jupiter’s ring system before performing the first of its gravity assist maneuvers, and moving on to its moons. Scientists didn’t have high expectations; they thought that any moons here would be static, dormant worlds, much like our own moon. Instead, they saw that Europa was smooth instead of cratered, which led them to believe that it might have an ocean beneath an icy crust, and that Io had an active volcano (that they named Pele, after the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes), spewing a lava plume over 250 kilometers into space. They also got their first sight of Jupiter’s ring system.

Saturn

In the fall of 1980, both Voyager craft got their first close view of Saturn and its famous rings. Unfortunately, the camera platform on Voyager 2 had locked up from the cold, and only by slowly moving back and forth a little bit at a time were they able to loosen it enough for it to work properly again.

Then it was time to move on to the moon Titan. Titan was extremely interesting to scientists because it seemed as though Earth might have originally been much like Titan. Though Voyager’s cameras couldn’t see through the thick clouds of Titan, radio signals could get through, giving us a lot of information about the moon, including its size, atmosphere, surface temperature, and air pressure.

Uranus

At this point, Voyager 1 moved out of the planetary orbit path, and Voyager 2 got another gravity assist maneuver to boost it toward Uranus, where it arrived in January of 1986, less than a decade after launch. Without all those slingshot boosts from the previous planets, Voyager would have taken 30 years to get to this point.

And of course, Uranus had surprises of its own. For all the other planets, the pole of the magnetic field is near the rotation axis—what we would consider a north or south pole. Not Uranus, which not only spins on its side, the magnetic pole is near the equator. Voyager also discovered new rings and new moons around Uranus.

Neptune

After another three and a half years, in the summer of 1989, Neptune was coming up. Voyager had to be reprogrammed in order to operate in the colder, darker environment. The capability to get images from that far away hadn’t even existed when Voyager launched, and required multiple large telescopes to receive the weak signal. The most unexpected  revelation from Neptune was the Great Dark Spot — at least until the moon Triton came into view. Triton, with geysers of nitrogen gas erupting five miles into space.

revelation from Neptune was the Great Dark Spot — at least until the moon Triton came into view. Triton, with geysers of nitrogen gas erupting five miles into space.

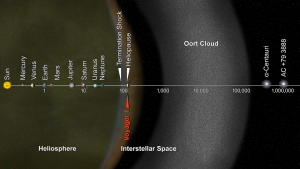

Beyond

A magnetic field extends like a bubble around our sun (and other stars, too). It’s called the heliosphere, and no one knew how far out it extended. That is, until 2012, when Voyager 1 (remember, that’s the one that is moving the fastest and has gone the farthest) popped out of the bubble and entered interstellar space. It was the first thing built by us that left the solar system. Both Voyagers still communicate with Earth nearly every day, though the signals are less than one-trillionth of a watt, and someday, even those will go silent.

Before leaving the planets behind in 1990, NASA scientists turned the cameras, looking back in the direction they’d come from, in order to get a final view of the planets of our solar system.

As of April 2020, Voyager 1 is over 13.8 billiion miles from the sun, and Voyager 2 is 11.4 billion miles from the Sun. Both spacecraft communicate with Earth nearly every day, though the signals are less than one-trillionth of a watt.

And still, even now, in the space between stars, Voyager still has a mission. Someday, perhaps millions of years in the future, when we as a species have disappeared or evolved into some new type of human, this record of our existence may still be found, and someone, somewhere, will know we have existed.

New Horizons

Voyager had been incredibly successful, and NASA decided that more exploration of the far points of the solar system was in order.

The Mission

More than 40 years after the launch of Voyager, the New Horizons spacecraft began its mission of exploring Pluto, its moons, and the Kuiper Belt.

The Launch

New Horizons launched from Cape Canaveral on Jan. 19, 2006. Previous launch attempts were thwarted by a power outage and high winds, but the third try’s the charm, and New Horizons made it safely into space.

Jupiter

Though not part of its main mission, New Horizons swung by Jupiter to get a gravity assist in 2007. While there, it passed the biggest planet at less than 1.4 million miles from its surface. It also got pictures of the moon Io, including images of the Tvashtar, Prometheus, and Masubi volcanoes. The plume of Tvashtar (the Hindu god of blacksmiths) was 180 miles high, and had fallout bigger than the state of Texas!

Pluto

Remember the communication delay we talked about back in our first module, the Aquarius Habitat? That’s what happens when it takes time for a message to get from a spacecraft back to Earth because of the enormous distances involved. Obviously, the farther away a spacecraft is, the longer the communications delay is. By the time New Horizons got to Pluto, it took 4.5 hours for a message to get back to Earth, and vice versa.

Pictures from New Horizons showed a surprisingly young surface on Pluto, including a mountain range as high as 11,000 feet. Scientists believe that these mountains are only about 100 million years old at most, and are a result of recent geological activity on the surface. For comparison’s sake, Mt. Everest is about 29,000 feet high.

KBO 2014 MU69

In 2016, NASA extended New Horizons’ mission so that it could get a closer look at Kuiper Belt Object 2014 MU69. The New Horizons team took suggestions from the public for a nickname for this object, and settled on Ultima Thule (say TOOL-ie), More than three dozen different people suggested the nickname, but there was some controversy surrounding it. Though its original medieval meaning of “beyond the known world” seemed innocent enough, the term was also used by Nazi forerunners and modern extremist groups. Nevertheless, NASA decided to keep the nickname.

New Horizons flew past Ultima Thule on January 1, 2019. By this time, the communications delay was up to 10 hours. At its closest approach, New Horizons zoomed as close as about 2,000 miles. Ultima Thule is 21 miles long, and made up of two sections, joined to make a narrow “neck”. The larger, flatter section is “Ultima” and the smaller, rounder part is “Thule.” The pair most likely started out as two separate objects that gradually came together. The entire object appears red, probably because of deep-space radiation.

Upon its official discovery, the object got its official name: Arrokoth, a Native American term meaning “sky” in the Powhatan/Algonquian language.

What's Next

As of March 2019, New Horizons was about 4.1 billion miles away from Earth, cruising deeper into the Kuiper Belt at over 30,000 miles per hour. The mission is extended through 2021 to explore additional Kuiper Belt objects.; who knows what other mysteries it will shed light on?

Curriculum Reference Links

- Earth and Space / Building Blocks/ 1: Students should be able to describe the relationships between various celestial objects including moons, asteroids, comets, planets, stars, solar systems, galaxies and space.

- Earth and Space / Building Blocks/ 3: Students should be able to interpret data to compare the Earth with other planets and moons in the solar system, with respect to properties including mass, gravity, size, and composition.