UPR.F | Down, Down, Down We Go

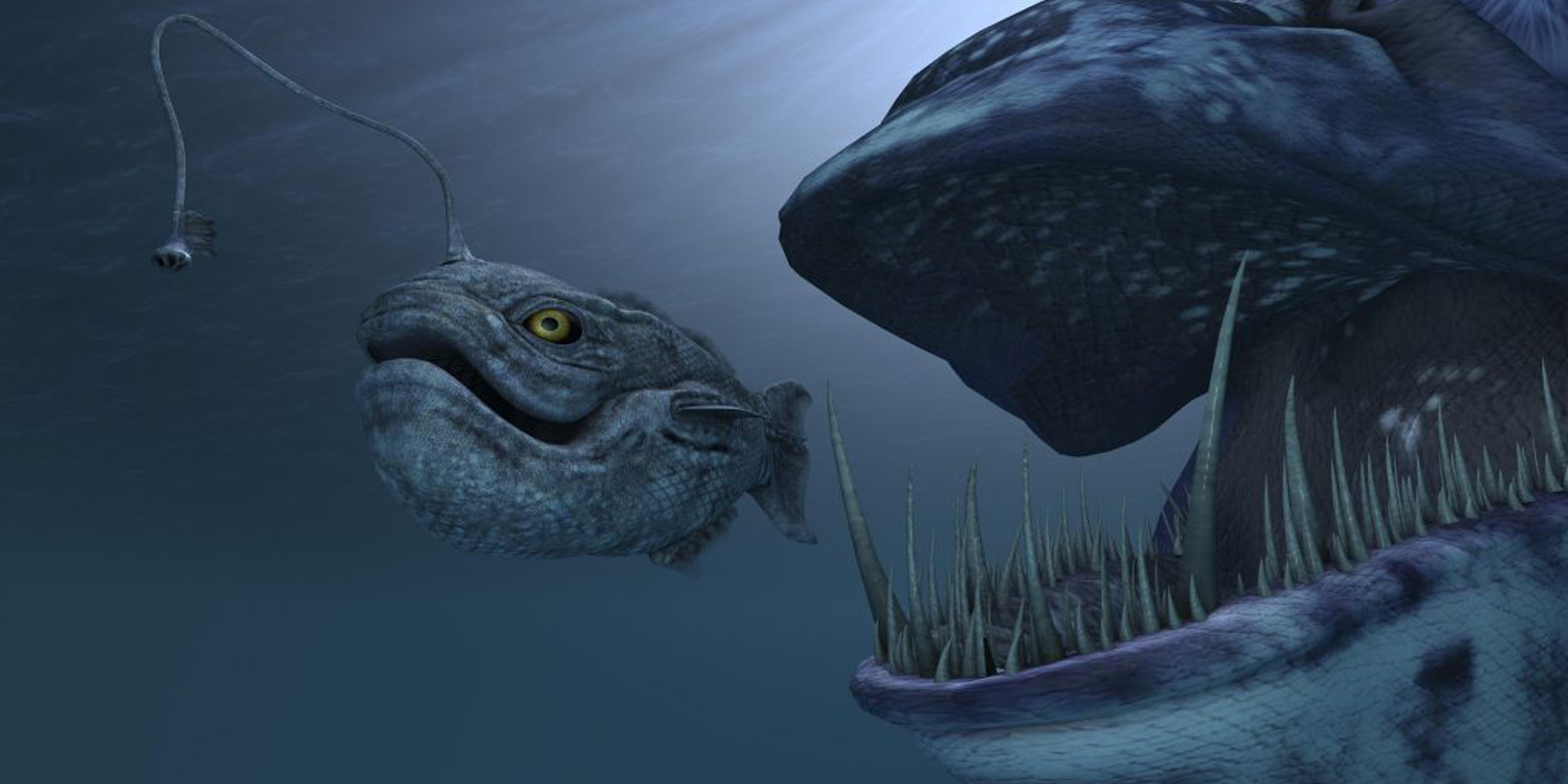

What happens when you go really deep? If you somehow ended up way down in the middle of an oceanic abyss, somewhere in the deepest parts of the ocean, you’d have a lot to worry about. It’s freezing cold, there’s a serious lack of breathable oxygen, there are weird creatures that might qualify as monsters…of course none of would matter, because you’d basically be squashed into something gooey and unpleasant to be around. The massive amount of pressure would compress your lungs far too much to work at all, along with keeping your heart from pumping.

What happens when you go really deep? If you somehow ended up way down in the middle of an oceanic abyss, somewhere in the deepest parts of the ocean, you’d have a lot to worry about. It’s freezing cold, there’s a serious lack of breathable oxygen, there are weird creatures that might qualify as monsters…of course none of would matter, because you’d basically be squashed into something gooey and unpleasant to be around. The massive amount of pressure would compress your lungs far too much to work at all, along with keeping your heart from pumping.

There have been a few people who have dived to some pretty ridiculous depths, including a man named Herbert Nitsch, who dived to 830 feet in 2012. But for practical purposes, most free divers don’t go below about 400 feet, and many of them suffer ill effects for doing so–little things like bleeding in the lungs, for instance. It’s very difficult to determine what the “crush depth of a human” is because the only way to do that would be to monitor a human until, well, they died, and then going backwards from there.

Not exactly optimal.

Pressure in the Hab

Down in the Hab, we work and live at about sixty-five feet beneath the surface, which means that the outside pressure is at two and a half atmospheres above that at the surface. But wouldn’t it be better to keep the pressure even with the surface? Wouldn’t that be more comfortable?

In fact, the exact opposite is true. Having the pressure inside the Hab being equal to the water pressure surrounding us actually allows us to have an open hatch in the floor that we call a “moon pool”. Ever pushed an empty glass down into the sink, open end down?

Notice how the air stays inside? That’s because the pressure is equalized and the air stays inside as long as you push straight down.

The moon pool in the Hab works the same way – the positive pressure inside keeps the water at bay. This allows us to come and go as we need without having to flood and purge an airlock every time we want to go outside. The other advantage to this is that living at the same pressure as the outside environment – where we spend most of our time working and conducting research – means that our bodies don’t have to equalize to the pressure outside the Hab.

It does, however, mean that when we prepare to head back up to the surface after a mission that has kept us at twice the surface pressure for two to three weeks, we have to spend 18 hours decompressing!

Curriculum Reference Links

- Physical World / Systems and Interactions / 3: Students should be able to investigate patterns and relationships between physical observables